A Toronto woman who waited 48 hours in an urban emergency unit can attest to the crisis doctors and nurses say is crippling emergency rooms.

"Until you are in it, you don't really understand how desperate and critical it is. Why everyone is not up in arms … that just is stunning. It's unbelievable," said Siobhan Mitchell.

She says she went to emergency in mid-August and was admitted for urgent gallbladder surgery, but there were no beds.

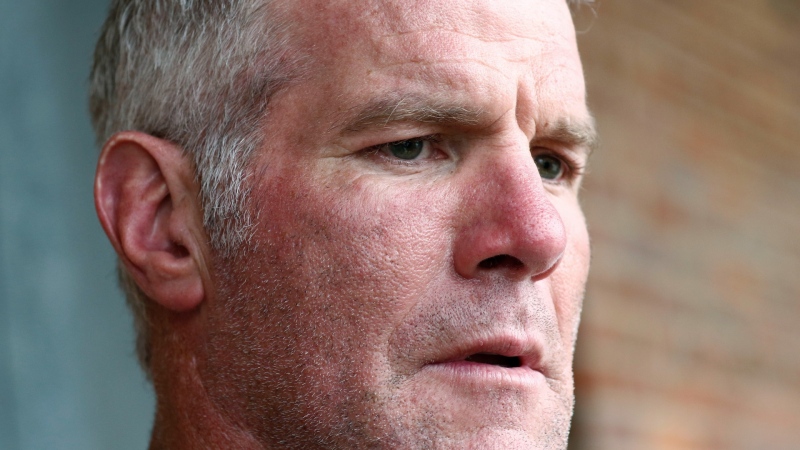

Mitchell waited for two days in a bed in the hallway. At one point, she snapped a photo of the other beds lining the hallway and says she was shaken by what she witnessed.

"There's just so many people seeking care, immediate care, critical care, urgent care," said Mitchell, who described the events on her social media. "There's just not enough beds, there's not enough room and the wait times because of the volume of patients seeking critical care are off the charts."

She praised the nurses and personal support workers for staying calm in the chaos.

Mitchell eventually got successful surgery but says people need to understand that what ER teams are saying about overcrowding is real.

"We need to support our doctors and nurses … and ensure that we raise alarms that this is happening in our communities, in our community institutions," Mitchell said.

"We've normalized this dysfunction within our hospitals," said Dr. James Worrall, an emergency specialist at The Ottawa Hospital and professor at the University of Ottawa.

"We've normalized the idea that it's OK for admitted patients to wait in the emergency department for hours or even days before they move to the appropriate in-patient care area. We need to say that this is not acceptable," he added.

A photo from Siobhan Mitchell shows patients in the hallway of a Toronto hospital.

A photo from Siobhan Mitchell shows patients in the hallway of a Toronto hospital.

A new study based on data from British Columbia shows that ERs have seen "a sustained increase" in emergency visits three years after the start of the pandemic, as researchers track some of the longer-term impacts of the pandemic.

The data shows that emergency visits, which dropped sharply early in 2020 because of pandemic restrictions, returned to largely traditional levels within a year but have since grown.

The study also found ER department use grew at rates higher than the growth of the country's population, while higher numbers of patients were admitted to hospital for more serious diseases.

"This paper confirmed what a lot of us have seen on the front lines over the last two years," said Dr. Catherine Varner, an ER doctor and deputy editor of the Canadian Medical Association Journal who reviewed the study and wrote an accompanying editorial.

"Across Canada, we've seen unprecedented (ER) crowding through the summer. We feel like we're in a constant state of surge capacity and crisis management."

Data from B.C. also shows that waves of patients seeking ER care historically seen around flu season -- which traditionally lasted from a few days to a few weeks -- are now weeks if not months, said Varner.

"So it means that emergency departments are having to operate in this surge capacity state for much longer periods of time, which is exhausting to staff," she added.

ER units have also become what Nova Scotia ER doctor Tania Sullivan calls “the only default care space for all things.”

“You don't have a primary care provider? ‘Go to the ER.’ You can't see your specialist for a month? ‘Go to the emergency department.’ So it is absolutely no wonder that we appear to be in crisis,” said Sullivan, who heads the emergency department at St. Martha’s Regional Hospital in Antigonish.

It bolsters a picture reported by ER doctors of overflowing emergency units, with more requiring a hospital bed than there are available. So they lay in the ER waiting.

"We often start the day with more than 30 admitted patients in the ED (waiting for rooms)..., which paralyzes us," Worrall said, adding that this leaves emergency teams with only a handful of ER beds for new emergencies.

New data from CIHI shows that these admitted patients in ER are waiting longer to get into an acute care bed. In the 2021-22 period, 90 per cent of emergency patients waiting for a hospital bed got one within 40 hours. Data from 2022-23 shows that wait time has grown by nine hours to 49.

HIDDEN HARMS OF ER OVERCROWDING

Emergency units are designed to work like a tube where patients go in and are quickly assessed, treated or moved to rehab, a hospital bed or home. They are not designed for people to stay there for long periods.

As new emergency cases come in, there is nowhere to care for them.

Doctors reported to CTV News they've treated patients in waiting room chairs and bathrooms. One doctor even said he resuscitated a patient in the EMS van because there was no room to revive the patient in the ER.

"We … have to see patients in these unconventional spaces, like driveways, like closets, that patients don't expect and they certainly deserve better," said Varner.

A sign advises hospital patients of the closure of a public washroom.

A sign advises hospital patients of the closure of a public washroom.

Nurses too report added stress caring for additional patients in ERs.

“It's usually like one nurse to four patients, as long as it's not like a trauma or a vented patient. But when you have overcrowding, sometimes that might be one nurse to eight patients in the ER, and that’s where it gets scary, where people don't feel comfortable. Being able to manage that,” said Dawn Peta, a registered nurse in Lethbridge, Alta., and co-president of the National Emergency Nurses Association.

Earlier this year, ER doctors in Alberta and B.C. sent out letters warning patients not to come to emergency, saying overcrowding caused by lack of beds and staff might boost the risk of medical errors.

Several families reported in 2023 that their loved ones had been harmed or died likely because of ER overcrowding.

Allison Holthoff was one of them. The 37-year-old mother waited for seven hours for care at the Cumberland Regional Health Care Centre emergency in Amherst Nova Scotia on Dec. 31.

“She said, ‘I think I’m dying. Don’t let me die here,’” said her husband, Gunter.

Worrall suspects there may be many more cases like this that aren’t made public.

"The extra deaths caused by emergency department crowding are so rarely counted because it's hard to pinpoint the crowding as the proximate cause of the death. But when you look at populations and population-level data, you clearly see excess hospital deaths when emergency department crowding is worse," he said.

He and colleague Dr. Paul Atkinson from the department of emergency medicine at Dalhousie University in Halifax tried to put a number on what they called a "hidden pandemic" of harm.

They used a formula devised by the U.K. Royal College of Emergency Medicine and The Economist to assess the increased delays in moving patients out of the ERs into the hospital beds in that country.

The U.K. data suggested that between 260 and 500 patients a week may be dying in excess of what would be expected when ERs are crowded.

"If you do simple multiplication based on our population, you would find that over a year, somewhere between 8,000 and 15,000 patients are dying in Canada because of emergency department crowding," Worrall said.

It may be a speculative exercise, but it is designed to catch the attention of health regulators and the public.

"Right now, as I see it, that accountability is lacking. We just blame a lack of money, a lack of nurses. Nobody is actually responsible for fixing that problem in real-time and making sure that capacity is preserved," Worrall said.

SOLUTIONS

Everyone CTV News spoke to agreed that while COVID-19 made things worse in hospitals, it isn't the sole reason behind the overcrowded ERs.

The rise in demand is linked to a growing and aging population, as well as staffing shortages caused by an exodus of nursing and medical staff during the pandemic.

More in-hospital beds is clearly one solution, Varner said, who points to data from the OECD showing Canada has among the lowest hospital bed-to-population ratios of some developed countries.

"Why are there not more acute care hospital beds and staff to care for patients that need hospitalization and why are we not trying to retain our experienced hospital staff, who unfortunately have been burned out through the course of the pandemic and the years that have followed? These are questions that I asked often and don't receive a lot of answers to," Varner said.

Worrall agrees there are also inefficient hospital systems that need to be redesigned.

"Money is very welcome throughout the system, but I don't believe it will have a meaningful impact on emergency department crowding. Because we're going to keep doing things the same way we always have, we're not going to change the way we choose to move patients through the system," he said.

Earlier this year, the federal government gave the provinces and territories an immediate, unconditional $2-billion Canada Health Transfer on top of a record $198.6 billion to address immediate pressures on the health care system. But there were no strings attached on how it would be used.

"As a health-care team, we are disheartened, dispirited and have lost all hope that our leaders even understand the magnitude of the issues that face us. God help us all," said veteran ER doctor Alan Drummond, the past president of the Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians. His group is calling for a national forum to come up with a cross-country plan to fix the problem fast.

"This would not allow each provincial government to ... continue the current approach ... with no chance of success," he said.